This post is part of the Criterion Blogathon hosted by Criterion Blues, Speakeasy, and Silver Screenings. Be sure to check out all the awesome posts here!

Men didn’t cry at the movies in 1955. Not after what they had been through in Europe, the South Pacific, and Korea. It is difficult to imagine these war veterans tearing up over an impossible love affair between a rich widow and her young gardener. Such stories were for the women, and so they were called ‘women’s pictures,” signaling the men to stay away. Never mind that these movies were often tough criticisms of social and domestic hypocrisy. Social problems were best discussed at town meetings. Movies, at least the ones designed for men, provided a retreat into memories of adventure, bravery, and heroism. They left a man feeling good, not all broken down and choked up.

Movies that hooked into one’s emotions were despairingly called “tearjerkers,” and a man would rather be keel-hauled through a school of sharks, or tied to the mast of a sailing ship during a hurricane, than to allow his emotions to be manipulated in public by a Douglas Sirk movie. Hell, even his war movies, with reflective protagonists played by soft-spoken actors like Rock Hudson and John Gavin, were tearjerkers. Can you imagine a group of Korean war veterans getting together to share a good cry over the struggle of an ex-bomber pilot to rebuild an orphanage he had accidentally destroyed in the war? Not likely. Such a reunion was more apt to take place in a movie theater showing Hell in Korea, Men in War, or China Gate.

Things are different today. A guy can sit in a movie theater and bawl his head off all the livelong day and nobody is going to question his manhood. Not that “All That Heaven Allows” is a ‘bawl your head off’ movie. It’s more of a gentle weepie with an undercurrent of disdain. Now “Imitation of Life,” that was a picture that would make you bawl your head off. But you wouldn’t do it in public. Not in 1959. Today you would, but not then. “Imitation of Life,” despite being one of the most passionate screeds against racism ever filmed, was a ‘woman’s picture,’ and the only reason a man had for attending was to provide comfort for his wife or girlfriend while she bawled her head off.

I go on about this for the purpose of establishing how director Douglas Sirk was perceived by the public during the final decade of his career, which might explain why his present reputation in the United States is sometimes sullied by the misapprehension of his work as ‘camp’ of the ‘so bad it’s good’ variety. In one of the first reviews of “All that Heaven Allows,” New York Times critic Bosley Crowther dismissed it as a “frankly feminine fiction” in which “one of those doleful situations so dear to the radio daytime serials is tackled.” For the most part, today’s critics have been more appreciative, although if you venture into a cinema where it is being screened, you are apt to encounter some rather ignorant heckling by inebriated clubbers going through their “ironic phase.”

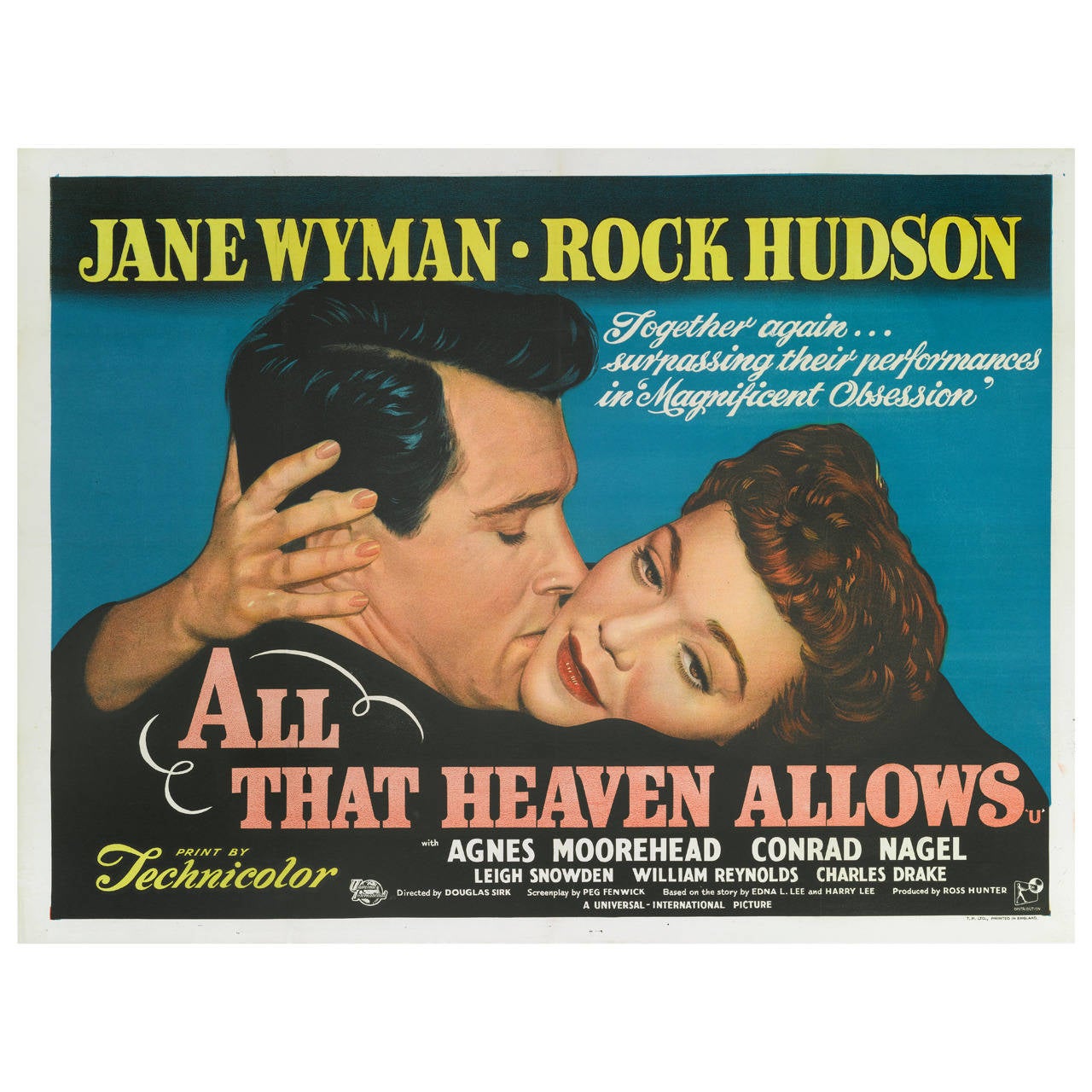

“Consolation #3 in D flat” by Franz Liszt underscores the opening of “All That Heaven Allows,” in which a crane shot overlooks a small town in autumn from the height of a church steeple. The music continues to develop throughout the film, creating emotional dynamics even when Rock Hudson’s Ron Kirby and Jane Wyman’s Cary Scott remain physically impassive. Kirby’s insistence that Scott places love above social convention recalls Gary Cooper’s sternly immobile performance as Howard Roark in King Vidor’s 1949 film of “The Fountainhead.” Like Roark, Kirby is willing to sacrifice a love affair rather than compromise it. And like “The Fountainhead’s Dominique Francon, Scott endures much suffering until she is able to accept and embrace the terms of an uncompromised love.

Agnes Moorehead plays Scott’s best friend, Sara Warren, whose conformist nature is represented by the color co-ordination of her blue dress with her car. Russell Metty’s cinematography works hand in hand with Russell Gausman’s set design to establish relationships between characters, as well as between character and both private and social environments. For example, Scott attends a formal event at the country club in a low-cut red dress, which recalls Bette Davis’ insolent wearing of a red dress in William Wyler’s 1938 film, “Jezebel,” indicating that Scott possesses a rebellious nature that has not yet been made explicit in the script.

Sirk also uses vitral windows to isolate color. In one instance Scott’s children are partially obscured in deep blue shadows while Scott is bathed in a yellow light. But characters are not consistently identified with a particular color. The blue shadow behind the children may well encompass their mother in a subsequent camera set-up. In another case, the vitral window casts , to no apparent purpose, a the colors of a rainbow upon a bed covering. So there is a crazy wildness to the color scheme that prevents easy interpretation, pointing toward a hallucinogenic freedom in the representation of enclosed spaces.

If the color scheme of the Scott household represents a clashing of the personalities within, the consistency of tone in Kirby’s environment, which includes the home of his close friends Mick and Alida Anderson, suggests a harmonious aggregation of diverse social types. There are no rigid codes to which all must adhere. Rather, each person is accepted on his or her unique terms. Even Scott herself is not ready to accept those of different classes so freely. Despite her feelings for Kirby, she still sees him as the son of her former gardener, and continues to place herself in the superior position. As one character sees it, she is ready for a love affair, but not ready for love. In other words, she is unable to completely subordinate herself to the situation in which she finds herself.

When her children voice their objections to her marrying Kirby, Scott is somewhat sympathetic to their positions. Her son points out her obligation to his father’s memory, as well as the imminent loss of the family house such a marriage would entail. He daughter complains that “you love him so much that you are willing to ruin all our lives.” Scott’s initial reaction to Kirby’s proposal was that she would be turning her back on every thing she had ever known, and she was right. Until she is prepared for such a sacrifice, she will not be ready for love.

When all the obstacles preventing her marriage to Kirby prove to have been transitory, she comes around to sharing Kirby’s belief that nothing matters except for their love. Everybody who stood against them, including her children and best friend, had simply been venting their selfishness and hypocrisy. The town, which appeared so lovely in the film’s opening shot, is now clouded by the darkness of winter. The television set that her son has given her as a Christmas present to keep her from being lonely is an empty sheet of glass reflecting a flame from the fireplace and a tragic portrait of herself as a lost and loveless woman.

She learns that Kirby has been injured in an accident, and goes to him. The old mill that he had renovated into a home for the two of them is gorgeously illuminated in light, shadow, and color. He lies in bed, his body broken but his faith keeping him alive, and sees she has returned. Many people have expressed dissatisfaction at the film’s closing image, that of a deer outside the picture window, returning to the place where his injuries were healed. And sure, if you try to explain the meaning of this image, it sounds pretty corny. But the image itself, this deer in the snow, is so overwhelming that its beauty contains so much more than any meaning one might ascribe to it. Each time I see the film, I anticipate the return of the deer, and each time the deer appears at the window, and sees that all is well inside the house, I find myself peering in through the window, just like that deer, and the knowledge that Cary’s struggle is over, that she has finally learned what it means to love,all that is to be gained by it and how little can be truly lost….brings tears to my eyes, and I feel happy that our definitions of masculinity have evolved to the point where movie like “All That Heaven Allows” are no longer disdainfully regarded as ‘women’s pictures,” but are prized for the poetic spirit that breaks through all defenses to bring tears to the eyes of every one of us.